My mind’s feverishly grinding chunky blocks into tasty visuals as my joystick coaxes a blur of pixels and limited colours towards a new high score. Its basic appearance belies the epic drama unfolding inside my cranium.

There really was no so such thing as a “casual” computer or videogame. Each and every release demanded its fair share of devoted attention and reverence, whether it engaged players in interstellar shoot outs with invading space ships or text-based conundrums waiting to parse the user’s hopefully problem solving command. Human imagination transformed ill-defined pixel clusters into great drama.

“Going to the movies”, on the other hand, was akin to luxurious travels to faraway places warranting elaborate reports upon return.

“Going to the movies”, on the other hand, was akin to luxurious travels to faraway places warranting elaborate reports upon return.

Purchasing a ticket to see the latest sensation was in itself exciting, but the added surprise of experiencing the first glimpses of an as yet unannounced, possibly rumoured motion picture was unparalled in its effect. It was not at all uncommon for such trailers to dominate conversations after the show. Such an organic promotion rested on the scarcity of information in an age of incapacitating communications technology.

What is gained in technology is lost in imagination

For lack of forms of communication commonplace today, film thus activated the mind substantially, made it digest the sensations briefly flashed and hardly imprinted on a filmgoer’s memory. Once again human imagination was required to re-envision the perceived visuals verbally, crafting an exciting tale from only a smidgen of information.

Over the course of several decades, technology has considerably removed the glamorous sheen from video games and motion pictures. The former stumble towards photorealism at such an alarming rate, only the reflexes seem challenged. The latter have evolved into readily available commodities and are instantly sharable by virtue of the Internet. There is effectively no more need for communication, which has been overrun by the urge for one-way media consumption.

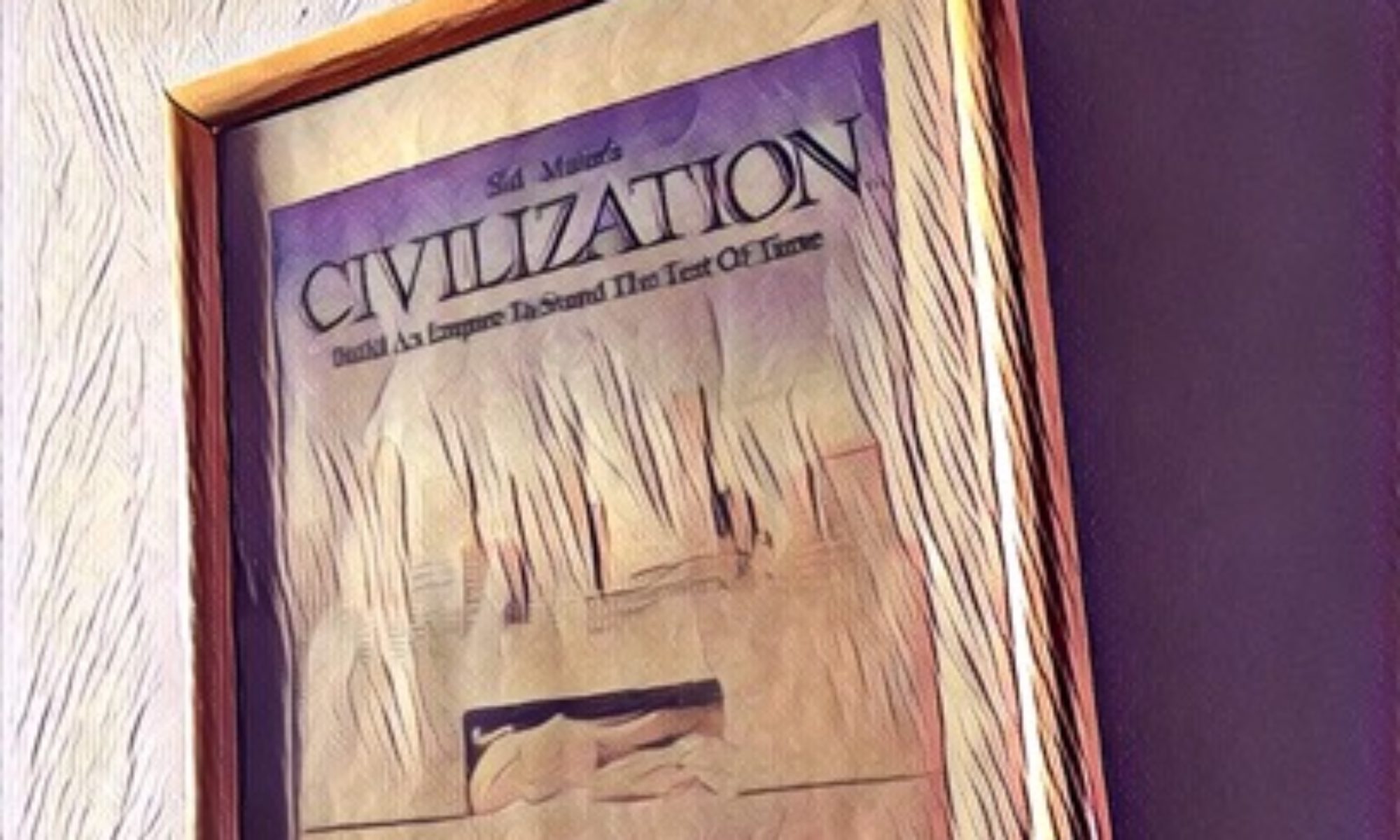

Retro is a watershed for an era when the entertainment industry was augmented by personal imagination and communication. Neither the games industry nor the filmmakers could afford not to be organically promoted by people longing to express their experiences.

Retrography lifts substance from the mists of the past that harbours, invites and promotes, as a matter of fact, human ingenuity.

Shadows of the Empire fan film on Kickstarter!!

Please support the project and share it with people! Thanks!!

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/392447955/star-wars-shadows-of-the-empire

Here is the Facebook page, share it if you can please!

https://www.facebook.com/StarWarsShadowsOfTheEmpire